(Quotes and references from tshaonline.org)

Situated about ten miles southeast of San Antonio lies a town site known as Southton, Texas. It was settled in the early 1900s on the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway. Today, the Southern Pacific Railroad off U.S. Highway 281 runs through Southton. Traveling toward Floresville on Hwy 181 or toward Corpus on IH 37, one might venture off the path a couple miles to discover Southton.

By the year 1910, the population of Southton had reached sixteen, and a post office was established. By 1940, the town had grown to include a church – the residents were mostly Lutheran – and a school. Its population had reached twenty, but it increased to some ninety by 1946. The rail station had become the shipping point for the Yturri-Southton oilfield, and it was the site of the San Antonio Cotton Mills and a detention home for boys eventually called the Bexar County Boy’s Home.

But in the years prior to the 40s, Southton developed a dubious reputation. In April of 1915, newly elected San Antonio County Commissioner Judge James R. Davis fulfilled a campaign promise to build a “new home for the indigent and the elderly.” A pauper’s home had been established in San Antonio in 1861 and was located on an 18-acre tract at the end of the Tobin Hill street car line. A wooden structure housed these indigents, and its condition had not only fallen into disrepair but was overrun by rats and insects. It was decided, however, that the site was insufficient for building a new, self-sustaining structure.

So, the county decided to build on 350 acres on the southern-most area of the city, which would be in the community of Southton. The new structure would not only serve as a Home for the Aged, but it would also serve as a Juvenile Home and Training School for boys between the ages of six and sixteen. The facility, which was shaped like a “T”, had quarters that were very plain, but those who had lived in the old pauper’s home were excited about living in a new location that had electricity, steam heat for hot water, a barber shop, and a surgical facility. Residents who were healthy and able were expected to work on the property, which included pig pens, chicken coops, and Jersey cows. As such, the facility would not be a “burden to the tax payers.”

Interestingly, the oldest resident to move into the new Home for the Aged was a 120-year-old woman named Juanita Rodriquez who had lived in Texas since before the siege on the Alamo. She had moved into the old pauper’s home some five years prior when “the shack that she lived in on the banks of the [San Antonio] river was washed away, leaving her homeless.” Reportedly, she was quite excited about moving into her new home.

When the other part of the facility, The Juvenile Home and Training School (also referred to as a factory) opened, it was presumed to be a home to help boys who had gotten into trouble by giving them guidance and training and thus “turn bad boys into good men.” Those boys who appeared not to reform would then be sent to Gatesville.

The factory would provide training from state of the art classrooms, recreation facilities, and vocational education. The dining hall could seat 40-50 people. The sleeping quarters would sleep 80-100. A guard was posted in the sleeping quarters at night where the windows were barred; every door had double locks; and the only thing in a boy’s possession during the night was his night shirt. All of this, along with the fact that the sleeping quarters were located on the second floor, was designed to keep the boys from running away during the night. So, the “school” was more of a prison for young men.

Another facility built on the grounds was The Tubercular Colony. There was no solid structure for these residents; instead, it was constructed of tents that could be easily moved or destroyed. The patients lived in tents until they succumbed to their illness.

For many years, people have conjectured that the entire area is a haunted asylum. Perhaps that is because it is said that there were many people placed in unmarked graves on the property, and, although death certificates show that many residents died there and were buried in the Home for the Aged Cemetery, “no cemetery on the property” has ever been discovered.

There seems to be no record as to when the entire facility was closed down; however, the Bexar County Boy’s Home – so renamed at an undisclosed time – was still in operation in the early 60s. Today, the property access has been blocked, and the buildings are dilapidated and dangerous. “Anyone caught on the premises could see a very stiff fine.”

Unrelated to the facilities described, there is another harrowing legend of Southton’s being haunted. Accordingly, in the 1930s or 40s, a school bus full of children stalled on the tracks in “downtown” Southton and was hit by a freight train, killing many of the children and the driver. Folklore says that “if you park your car directly over the tracks heading west, shift into neutral and put powder on the back of your car for proof, the ghosts of the children will push your car uphill and out of the way of the oncoming train.” Legend also has it that “they leave their fingerprints behind” in the powder on the back of the car. Of course, non-believers have scientific proof that explains this phenomenon, and some reports claim that this tragic accident did not even happen in Southton, but the legend makes for a much more exciting tale.

There is yet another tragic Southton incident which is not folklore. Around the bend from the above-mentioned facilities stand the remnants of the San Antonio Cotton Mills. In the mid 50s, a juvenile named Frankie Harris was passing through the then abandoned grounds and stepped on a live wire that had fallen after a recent storm. Frankie lost his life instantly, dying of electrocution. Because this writer – who was around ten years old then – lived in the Southton community at the time, she well recalls that tragedy and its sad effect on the residents of the community.

A pleasant memory of the community is the post office which was in a private house. The resident of the home and postal clerk had a barred window on her front porch, and residents would knock on her door to be met then at her window through which she would hand over the mail. A child always found delight in gathering mail for its parents.

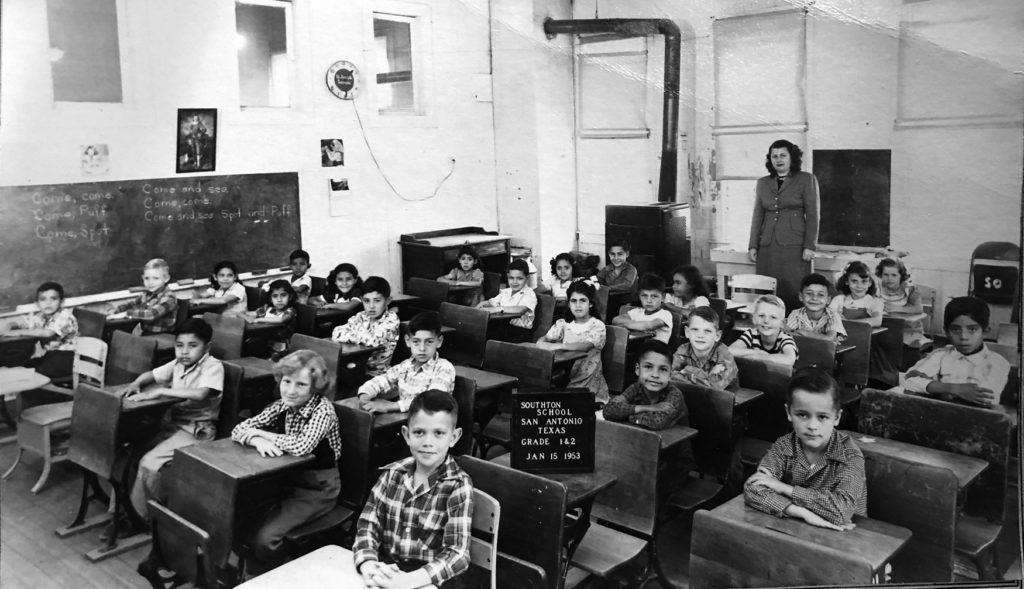

The school that was built in those early days of Southton was in operation through the 50s. It consisted of three rooms and six grades, one teacher and two grades in each room. Mrs. Williams, this writer’s teacher, taught first and second grades. Third and fourth grades were taught in the next room; fifth and sixth grades in the third room. The principal, who was one of the teachers, was a Ms. Hays. As with so many former schools in Medina County, like Shook, Biry, Big Foot, Dunlay, etc., children walked to school – or rode bicycles. And everyone was safe. The biggest concern was someone’s protective dog chasing a child. Or, as in one specific case, a dog who chased a bully who was throwing rocks at his friend, a little red-headed girl, as she rode her bike by his house!

Southton today has a little over a hundred residents. Many of them went to school in the community – Southton and Harmony elementary schools, Oak Crest Junior High School, and East Central High School. Some of these children finished school in Floresville ISD when East Central lost its accreditation for a short time. But, many of these grown-up children returned to the Southton community to raise their own children on family properties. The Smith family of girls – Lou, Shirley, and Margie – are examples. And those who spent their childhood years growing up in the Southton community then moved away very likely harbor sweet memories of those impressionable times.